Is it any wonder that not one but two words in English for a social climber—arriviste and parvenu—come from the French? Our language is peppered with borrowed terms that provide nuanced derision in respect to class and wealth: nouveau riche, bourgeois, and gauche are but a few.

I can see why the French economist Thomas Picketty, who has made his name with a study of wealth inequality, was fascinated with Honoré de Balzac’s novel Père Goriot. It’s as if Balzac’s characters epitomize many of these class-based pejoratives.

Balzac was one of the great fathers of the realistic novel. In The Human Comedy, a series of eighteen novels in which characters appear and reappear, he depicts the complexities of French society between Napoleon’s reign and the Revolution of 1848. As Dickens dramatized life in the sooty, foggy, wretched, have-and-have-not world of Victorian London, so Balzac documented the pompous, greedy, stratified and amoral society of Paris during the Bourbon Restoration. The French Revolution may have toppled the ancien régime, but deference to status and wealth never disappeared.

In Cousin Bette, my favorite of his novels, Balzac targets the power struggle between the sexes. Men may wield power through the laws and purse strings, but clever women survive by charming and manipulating them—husbands and lovers alike. As Balzac sees it, men are vain, foolish and lustful, making them easy marks of feminine guile.

In Père Goriot, Balzac’s focus is on love and money. Old Goriot, a widowed vermicelli merchant now living in a seedy boarding house, has doted on his two daughters all his life. Because of the large dowries Goriot provided them, both are married to noblemen and treat their father with shameful ingratitude.

Enter Eugène Rastignac, a law student from a “good” but impoverished family, who arrives in Paris to make his fortune. Settling into the same boarding house, he befriends old Goriot. Eugène’s one distant relation in the capital happens to be a baroness, and he relies on her to make his debut into high society. At a ball hosted by the baroness he meets one of Goriot’s daughters, the Madame de Restaud, and becomes determined to win her heart. When rebuffed (she already has a lover), he takes aim with a vengeance at the other daughter, the Madame de Nucingen.

Enter Eugène Rastignac, a law student from a “good” but impoverished family, who arrives in Paris to make his fortune. Settling into the same boarding house, he befriends old Goriot. Eugène’s one distant relation in the capital happens to be a baroness, and he relies on her to make his debut into high society. At a ball hosted by the baroness he meets one of Goriot’s daughters, the Madame de Restaud, and becomes determined to win her heart. When rebuffed (she already has a lover), he takes aim with a vengeance at the other daughter, the Madame de Nucingen.

It’s a cynical and very French interpretation of love that Balzac puts forth. Eugène—so intent on gaining a foothold in society—convinces himself that he loves Madame de Nucingen. And Goriot, in his fondness for Eugène and his antipathy for his sons-in-law, encourages Eugène in his seduction. Goriot hopes Eugène’s attentions will make his daughter happy and enable him to see her more often, or at least hear about her from Eugène.

Meanwhile, one of the more interesting characters in the book, the shady criminal Vautrin who also lives in the boarding house, expounds a truly cynical worldview. Counseling Eugène to marry an heiress (which he is willing to arrange for a fee), Vautrin whispers like the devil in his ear:

There are fifty thousand young men in your position at this moment, all bent as you are on solving one and the same problem—how to acquire a fortune rapidly. You are but a unit in the aggregate. You can guess, therefore, what efforts you must make, how desperate the struggle is. There are not fifty thousand good positions for you; you must fight and devour one another like spiders in a pot. Do you know how a man makes his way here? By brilliant genius or by skillful corruption. You must either cut your way through these masses of men like a cannon ball, or steal among them like a plague. Honesty is nothing to the purpose.

Vautrin nearly persuades the young student: “Vautrin is right, success is virtue!” Eugène says to himself in a moment of financial frustration. But he subsequently convinces himself that with Madame de Nucingen he can find both love and fortune; it’s this naiveté that Balzac gradually chips away through the course of the novel. No one comes away unscathed, except perhaps old Goriot, whose devotion to his daughters in the face of the most heartless cruelty is the least credible aspect of this retelling of King Lear.

Early on, Balzac hints at his theme in a description of the garden of the boarding house where Eugène, Vautrin and old Goriot live:

On the opposite wall, at the further end of the graveled walk, a green marble arch was painted once upon a time by a local artist, and in this semblance of a shrine a statue representing Cupid is installed; a Parisian Cupid, so blistered and disfigured that he looks like a candidate for one of the adjacent hospitals, and might suggest an allegory to lovers of symbolism.

An allegory, indeed. But not just for Parisians. Which may explain why so many of those derisive French words have entered our own language.

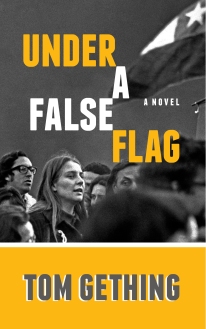

If Balzac writes as well as Tom Gething then I need to start reading Balzac

Ha-ha! Thanks, Ken. Balzac’s got very big shoes. BTW, you got an email on this because you are “following” me. If you don’t want to get them, just unfollow me. See you on the courts one of these days soon, I hope.

Remarkable spotlight dear Tom… “The Human Comedy’ was certainly a colossal attempt… I guess that Balzac writes as a russian writer, those minimalistic approaches… He reminds me of both Tolstoi and Chejov.

Always a pleasure to stop by, best wishes, Aquileana 😀

I hadn’t thought of it that way, but you are right. Balzac’s opus is as large a canvas as those big novels by Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky. As a whole, the Human Comedy captures as many strata of society as those great writers do. Thanks for the insight, Aquileana. Have a great weekend.

Aside from Tom Gething’s

Writing prowess,

What I love most

About his posts

Is his unbridled enthusiasm

For the written word.

Lovely, Russell. Thank you!

Père Goriot is my favorite Balzac! And one of my favorite books of all time. It was the first Balzac I read and started me on a mission to read the entire Human Comedy. Counting the novellas and the short stories there are nearly one hundred items in the Human Comedy. Then I had to read the plays, Droll Tales and any of his early pot-boilers I could find, lol. La Comedie Humaine blog here at WordPress is a good resource and fun to browse. There are several sets of illustrations for Père Goriot.

Wow! Thanks for the links. How cool that there’s a blog just about the Human Comedy. My next book of his will be Lost Illusions, but I’m afraid it will be a while before I get to it. Too many books to read. Thank you for reading and commenting.

You’re welcome. We try to spread the word. More stuff is still being added, but it’s already a pretty good resource.

Make a note to read Scenes from a Courtesan’s Life after Lost Illustions. The action in Scenes picks up immediately after the end of Lost Illusions and continues Lucien’s story.

Thank you, I will. By the way, I had to laugh at your avatar name. Very appropriate if Père Goriot is your favorite book.

LOL, thanks. That is exactly where it came from. I think non-Balzac readers sometimes get the idea that it might be a business account, lol.

🙂

As ever you are always reminding me I have good books that I need to get around to. This pleases Ste greatly.

I like all things French, particularly the words. French makes English sound better 😉

Hi Emma, me too. Especially when, say, Monty Python are speaking English in a French accent 🙂

I LOVE Monty Python! “This is an ex parrot!”

Or half a bee!